Medieval Manuscripts, Game Modding, and You

What the fourteenth century can tell us about videogames

Books aren’t real, and neither are games.

Hi, everyone. In this post, I’m bridging the gap between my two favorite subjects. More medieval stuff will come later, if you’re interested.

Today’s post fits within my tag “The Bourbonic Plague,” so I’m having a little drink and writing more casually about the Middle Ages. Today’s drink is not a bourbon. It’s a gin from Mother Earth Spirits in North Carolina, mixed with some tonic water, lime juice, and a lemon slice. Give a prayer to Tiw (it’s Tuesday) and Caesar (it’s July), and let’s talk about old dead guys.

What writing was like before printing

Before books were books, when writing was a privilege for the land-owning classes, there were no publishing houses as we think of them today. Getting your work out into the world required a few friends who were willing to copy out your work by hand and pass it along to their friends.

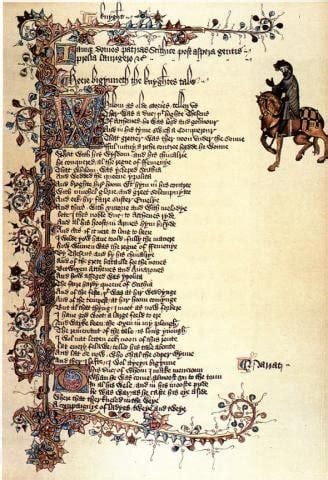

In that transmission, texts could change in a few ways, including: (1) handwriting mistakes; (2) adding in a short section for clarity; and (3) removing a section to avoid complexity or a disagreeable opinion. All of these alterations were common and expected.1 Other methods of change included unintentional damage (fires, floods, etc), theft, and book-burning, and of course the illuminations (illustrations) would change, but today I’m just focusing on the things that changed during standard textual transmission.

There was no such thing as a “canon” work until well after the printing press came to Europe.

Before the printing press, when everything was still handwritten and handbound into codices (which we call “manuscripts:” “hand-writings”),2 writing was neither static nor universal. The copy of Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Miller’s Tale (1390s) in your lord’s library would not be the same text as the copy in a library 30 miles away. Those two texts were written by different people, so even if (somehow) they kept every word the same, there would be a few spelling differences and different presentation within the codex.

For me, the coolest part about manuscript transmission is that, for most medieval works, we don’t know what the original author’s handwriting looked like. All that survive to the modern day (so far, we’ve rediscovered) are copies of copies. We know Chaucer wrote The Canterbury Tales because everyone in 1400 said that he did—but we don’t have his handwriting.3

The differences among Piers Plowman manuscripts are so extreme that scholars have needed to name and categorize disparate texts into groups, like gathering several animals into species and genera.

Piers Plowman has at least three genera. We call them A-, B-, and C-texts. Inventive. Scholars agree that these were all authored by Langland over the course of about 20 years, and they include his revisions. In a sense, all three are authoritative: the author was happy that each edition went out to the public. We can think of these as an early copy, a revised “definitive edition,” and a final “director’s cut” of the fourteenth-century religious dream vision about how corrupt the lords and clergy had become after the Black Death.4

The A-text is short and relatively simple. Easy enough. We have a few manuscripts of it, so we know it got around.

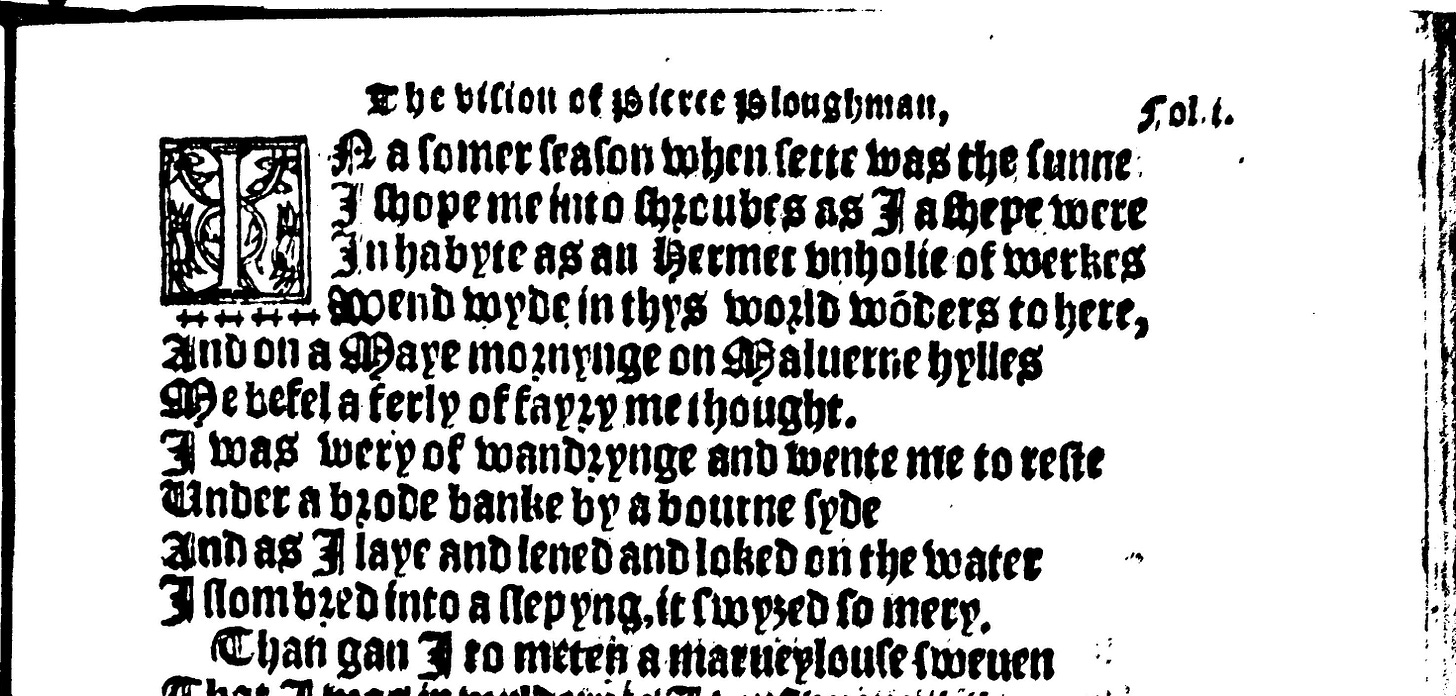

The B-text became a mainstream hit, as far as we can tell. It’s the version Crowley printed in 1550, so it became the most popular during the English Renaissance as well. It’s the version most often taught in medieval literature classes (if the professor is insane, like me). The B-text was quoted by John Ball during the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt. The words spurred on the riots and the attack on London, and Langland was (probably) mortified that his poem was being used to justify mass violence.5

The C-text is probably a final revision Langland underwent after the Revolt to distance himself from the whole “murdering of clergy” and “enemy of the king” thing. It is similarly popular. Scholars use this text a lot these days.

There is also a Z-text, but it was probably an earlier draft not intended for widespread reading. For more on the separate editions, especially within several copies of the B-text, see the Piers Plowman Electronic Archive, which is run by several great people, including former mentor of mine.

The point of all this: There is no one firm, official, correct version of Piers Plowman, and there never can be.

And we can never read Piers Plowman as Langland wrote it, even the C-text. We just don’t have whatever original copy he made and passed along to a friend. All we have are the copies his friends/colleagues made. Out of those, we try to create a critical edition—an edition that comes close to what the original was probably like. But it won’t ever be perfect.

This is true of every text before the printing press.6

When you mod your game, you take ownership over it

And your copy of the game is now entirely different from everyone else’s.

Live-service games and games that have had massive updates are infamous for the same idea: accessing Destiny 2 and Cyberpunk 2077 right now will give you an undeniably different text, different experience, than it would have five years ago. Because the developers have made changes, and the old versions are only accessible if someone happened to preserve them while they were active.

When you buy the definitive version of Mass Effect, you get something demonstrably and noticeably different than if you had bought the three games and their DLCs when they were originally released.

When you add a few mods to your Skyrim to make building your home not as burdensome, you are playing a unique version of the game. It’s just yours, even if you downloaded a mod made by someone else.

So, what’s the correct version of Skyrim? No mods, Legendary Edition? Just vanilla, the original release with no DLC? The Anniversary Edition with extra fan-made mods and (pretty cool) new content and mechanics?

The correct version is whatever you happen to be playing, just as the correct version of a medieval poem is whatever version your friend from Cambridge handed you at the feast last week.

Take power in the version you have. Experience several different versions, if that sounds fun. Choose an experience based on reviews and people you trust.

You have power, and the way you play is often up to you. Just remember that there isn’t only one version out there, even when we’re looking at the same code; adding our experiences together when we talk about a game should create joy and excitement, not frustration that someone else saw something that I didn’t.

A friend and I yesterday had fun discussing the negative ways corporations and some creators altered their original works. We can criticize Cyberpunk 2077, for sure, and George Lucas’s insistence that he needed to add as much CGI into A New Hope as possible (actually, even that name and the episode numbers were similarly messing with an original product). Can you think of any other media that you wish we could have the original form of, but that seems to be lost?

Be at peace.

Additions and redactions even happened to the New Testament’s earliest Greek manuscripts, and no one thought they were doing anything wrong.

A “codex” (pl. “codices” or “codexes”) is a stack of vellum, parchment, or papyrus bound on one side. They look like modern books. Codices did not include just one text, as modern books do. Since they were individually owned, written in, and passed down among the wealthy, the owners included whatever stories or texts they thought could fit. So you’ll get something like the famous British Library MS Cotton Nero A X/2, which contains four anonymous poems: “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight,” “Pearl,” and the less-known “Patience” and “Cleanness.”

I once heard it said that Shakespeare is the last author we know nothing about, and Milton is the first author we know everything about. And that’s basically true of Milton; we know all the major events of his life, his closest friends, his political beliefs, you name it. Shakespeare has gotten more tricky recently because we do have some biographical info on him. We know nothing or next-to-nothing about the vast majority of medieval authors.

Number one tip for reading books from 1360-1400: the author lived through the Death. Half of their friends died.

They didn’t call it the “Peasants’ Revolt” at the time; the word “peasant” didn’t enter English until the fifteenth century. English farmers revolted in 1381 for several reasons, which I won’t get into now. Several of the rebels even named themselves “Piers Plowman.” During the revolt, the rebels killed several royal officials, major lords, and priests.

It’s also true of Shakespeare. We don’t have official original copies of his scripts, even though we do have his handwriting in a few places. Many scholars believe that a few pages of a copy of Sir Thomas More has his handwriting on it. He also spelled his name at least six different ways, none of them the same as we spell it today. This is partly due to these being signatures, which were commonly abbreviated forms. My favorite is “Shakp.”

Oh man, that is a perfect example! I had no idea those versions were mirrored. I've gotta go back and play that one as an adult still

Dude... I gotta say: I've never related to a Substack post as much as this one! And I'm saying this as a guy who writes about business insights drawn from games and as someone who owns 7 different copies of Sun Tzu's The Art Of War just because each translation is unique. The way you draw parallels between how people had different experiences with manuscripts chopped from the same book and the game versions we play is fantastic. Really impressive stuff!

The only downside to your message is that I now have to choose between playing both versions of Link's Awakening back to back for the tenth time or diving into Umberto Eco's The Name of The Rose for the third time. Choices, choices...